Are we exploring the need for psychological and emotional safety in our healthcare relationships?

- Kit Wisdom

- May 6, 2020

- 7 min read

Updated: Nov 1, 2021

Do we all want to belong?

I recently heard a story that simultaneously broke and inspired my heart.

A few months ago, I met *Caty, a woman who had been suffering from back pain for over ten years.

She had spent the last 18 months at weekly physiotherapy appointments trying to 'fix' her back. She felt like her body was constantly failing her, as everything she tried did not seem to help. Every time she got ready to try again, she felt further away from where she wanted to be.

As a result, Caty exercised less and less. She was still fighting the pain, yet also felt like the pain was fighting her.

She was at war with herself - and her glorious vessel, her body - was taking the hit.

Caty felt powerless, lonely, and ashamed of the life she was leading. Because you see, Caty owned a personal training business. Her passion centered around empowering others to feel their best selves. Caty felt the best version of herself when she was physically strong and used exercise as a meaningful way to soothe herself in times of stress.

When her pain started to take away her capacity to exercise, she felt like it was really taking away her identity; taking away everything that made sense in her world, everything she cared about and lived for. She felt like the pain was robbing her of safety, leaving her anxious and uncertain; yet at the same time, she felt childish and ridiculous for feeling that way at 45 years of age.

When a space between stories presented itself, I asked Caty what it was about exercise that made her feel safe?

We sat together as she stopped and considered somewhat of a 'left-field' question. The silence became stillness. Neither one of us moved. Rawness filled the air.

She eventually replied, “my mum used to weigh me most days when I was a kid. She always had me on some kind of diet; her biggest concern was how much I weighed, not that I could ever be skinny enough ... so exercise is how I control my appearance. Exercise is how I cope.”

We soon discovered that Caty had been anxiously holding in her stomach.

For her whole life.

To hide her weight. To feel accepted. To feel loved.

I gently explained to Caty that abdominal bracing is a common fear-based coping strategy, that can potentially increase pain. I reassured her that pain is complex, layered, and unique to the individual. This meant that as a physiotherapist, I couldn’t tell Caty exactly what was causing her pain; but I could try and help her make sense of her experience.

Caty realized her bracing strategy was now the driver of her pain. Her need to fit in was now disconnecting her from herself. She had been trying to find a quick-fix solution, for a body that was holding on to a lifetime of emotional pain.

Caty’s lightbulb moment left her feeling vulnerable and self-critical, yet it also allowed space, for the first time, to move forward. By connecting the dots and making sense of her body’s response to pain and its fear of movement, we were able to create a new narrative around how Caty chose to move.

This happened by placing her story of self as central to her management. She needed to tell her story, as it was there that we found her answers. I needed her to value the importance of her story, as it played such a significant part in her healing journey. By providing space for the unattended parts of Caty’s story, we celebrated her complexity as a human and empowered her growth.

I often wonder how people would express themselves in certain moments if they knew that whatever they said or felt was not going to be judged.

I wonder how much people hold back from showing their true selves so as not to be embarrassed, invalidated, potentially seen as 'wrong' ... or maybe just even seen.

I wonder what it would be like if people felt that to show up as their full self was safe. Fundamental to being human. And really, fundamental to collaborative care.

In the field of physiotherapy (and other healthcare streams), where pain, persistent pain, and well-being are central to themes explored as part of treatment, a safe space to feel feelings, have a say, and be oneself is crucial.

Yet, potentially this does not happen enough. Or at all.

This sort of 'safety' is central to any kind of therapeutic relationship in order to build a connection based on trust, empathy, and genuine care. It is a fundamental teaching in the field of psychology however when it comes to physiotherapy and other healthcare fields, it appears to be sorely missed.

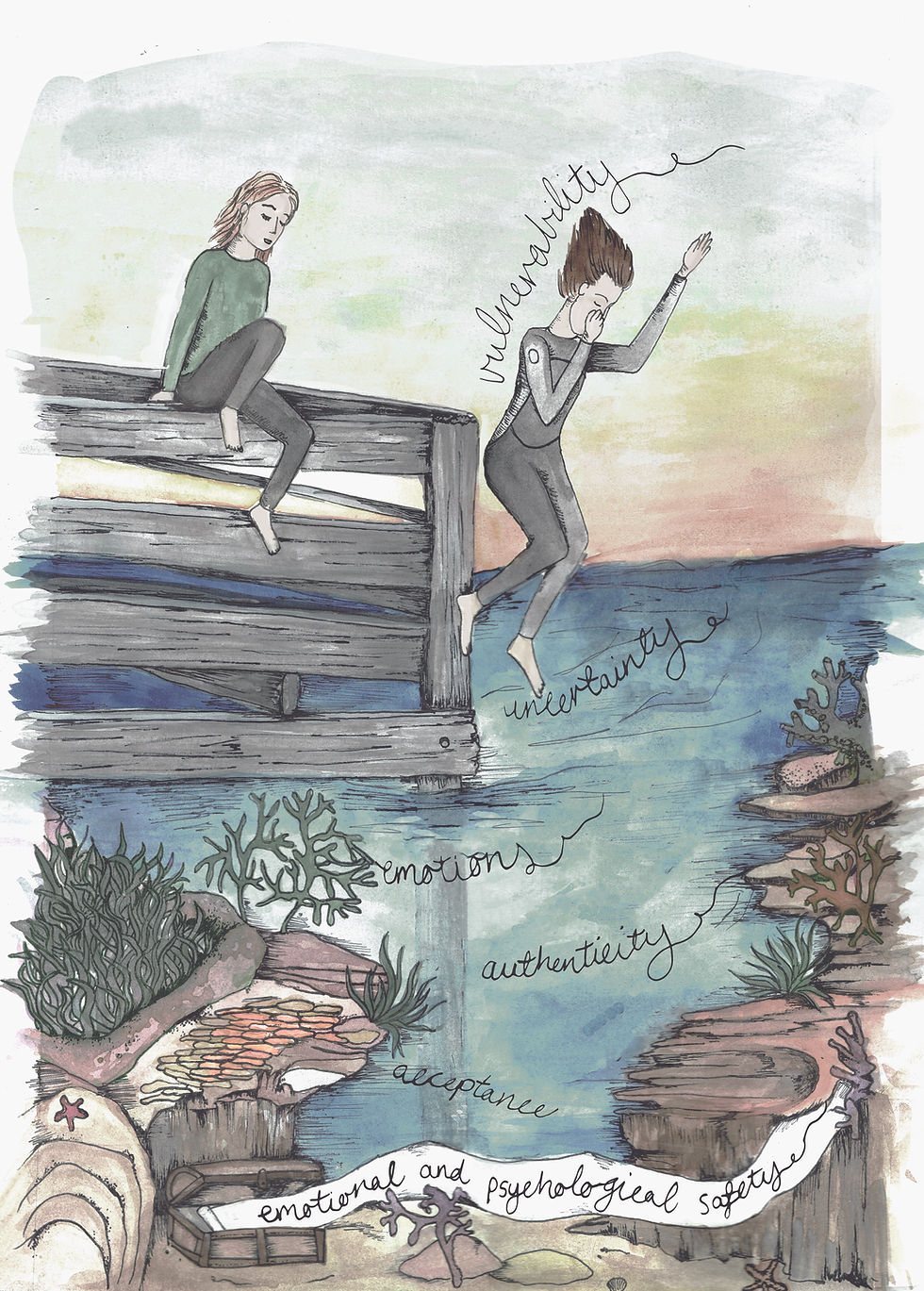

Psychological safety refers to an environment where people feel comfortable voicing their opinions and do not fear being judged. It sets the stage for a more honest, more collaborative, more challenging, and therefore more effective environment.

Emotional safety could be explained as radical acceptance of another's inner landscape; of how they think, of how they feel, of the stories that they tell themselves. Radical acceptance of all emotions.

This does not mean the safe space created is comfortable - quite the opposite. Such cultivated conditions engender a necessity for realness and this often takes the form of discomfort. For both the patient and the health professional.

Potentially the physiotherapy field has yet to really step into the discomfort associated with emotions because historically, we have been boxed into a physical domain centered around objectivity.

I find this so interesting, considering the official definition of pain from the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) firmly includes emotion as part of the "unpleasant (sensory and emotional) experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage."

Yes, our job is to create a safe space physically for the humans with which we collaborate. Yet we also need to value and create a safe space for emotions, for experiences, for relating, for realness, for more than just physicality; for humanness.

Otherwise, are we really holding space for what pain might be for another?

When I reflect on this need, it makes me think – when have we ever learned how to do this?

We have not been taught how to ask about people’s emotions.

We have not been taught how to explore difficult themes.

We have not been taught how to sit with people in their difficult emotions.

To sit with them. And not fix them.

We have been told that emotions impact pain experiences, yet not really shown how.

We may have heard some stories, yet where do we start? How do we start?

We have not been taught how to convey the importance and relevance of this.

Maybe we cannot see the importance and relevance of this.

Maybe we do not want to see the importance and relevance of this.

Maybe it is all too hard.

Maybe it is easier to stick to what we know.

We have not been demonstrated a way of knowing besides that of a detached, expert clinician who knows best about bodies.

And yet, all health professionals undertake emotional labour. All the time. We hold space for pain, anxiety, joy, loss, gain, unhappiness, belief, grief, anger, and pride - to mention only a few - on an hourly basis.

It feels like our field is ok to talk about discomfort in a physical sense, yet struggles to face and sit still in our patient's emotional discomfort. Relational discomfort. Social discomfort. Work discomfort. Trauma discomfort.

And what about ourselves?

Literature has started to explore the impact of our own emotional state on our clinical judgment. An important area of research that needs a voice amongst the information landscape. It requires being able to identify the emotions we are feeling and then taking the risk of actually feeling them.

Many of us may only be starting to create time and space to identify our emotions.

Many of us may be identifying them and then ignoring them, not sure what to actually do with them.

And many of us may not yet be in a position to start this process of observation.

Again, I am curious - when have we learned that this is important?

We have not been taught that to explore our patient’s emotions, we need to explore our own.

This has not been demonstrated to us, in how to do the exploring.

We have not been taught, led, or mentored in this way.

It has not been part of our CPD.

It has not been part of our process.

It has not been part of the healthcare professional deal.

Potentially, we are scared shitless to explore ourselves.

Because it feels hard. Because it takes time. Because it might be messy. Because it will probably never be perfect.

Because there is more than one way of going about it.

Because it requires stepping into vulnerability.

A place that has been ignored, suppressed, made fun of.

A place that is quite often seen as weakness.

Our delivery of care requires us to identify, feel, and synthesize our feelings, whilst considering our individual context. This means our own sh*t is central to care and we cannot run away from this.

Well, we can choose to run, but it might not help us in our intention to provide person-centered care. To help.

We are human aswell.

There is a tendency in healthcare to view clinical practice as a purely rational process. This worldview inhibits the contemplation of the potential impact of emotion on patient safety and subsequent care.

Clinical practice is about relationships. Dynamic, ever-changing, imperfect relational work. It involves the heart as well as the mind.

It's about how we relate to ourselves. About how we relate to those we are helping. It's about how we view these relationships.

Are they purely means to an end?

Or are we seeing these relationships as an expansion of self?

The way we choose to treat others is essentially a choice to help ourselves.

What does this mean if we are not choosing to pay attention to our own emotions, our own feelings, our own load?

Understanding that these sorts of explorations, expeditions into the unknown, tend to involve fear, uncertainty, and do not come with one specific answer.

This humanness - our ability to each be our own unique, messy, imperfect self - is our strength and gift as givers.

To me, this depth of humanness is calling out to be explored if we are to evolve our relationship with the care we so proudly provide.

Comments